article written by Isabelle Chéry and Jana Darwiche

A patent is an industrial property title that protects an invention and gives its owner the right to prohibit a third party from exploiting the invention.

a patent allows its owner to prohibit third parties from exploiting the invention protected by this patent; but a patent is in no case a legal authorisation for its owner to exploit the invention described and protected in the patent! Indeed, this patent may implement another invention protected by another patent. Before any exploitation, it is therefore necessary to study the freedom to exploit the patent.

A patent confers its holder an exploitation monopoly for a limited period of time (20 years) in return for the disclosure of the invention 18 months after filing. As a reminder (see P for patent: the basics), a patent describes a new technical solution that makes it possible to solve a technical problem that has not yet been solved or has been partially solved but with disadvantages that are overcome by the new solution.

- A description of the invention in its entirety, with a brief presentation of the drawings, if any. Drawings are not mandatory. The description sets out what is protected and what is free.

- Claims which define the legal protection scope and delimit the exploitation monopoly held by the patent holder. Not everything described in the patent is in the claims.

The patent also contains a summary of the invention. This summary has no legal value. The claims cannot be based on it. The summary must include the invention title, a concise summary of the essential features (it is practically a copy and paste of the first claim) and possibly indications as to the use of the invention. It may be accompanied by a figure.

- The description may be supplemented by drawings: it must enable the person skilled in the art to make the invention.

- Once the patent is filed, the description is intangible. No technical elements can be added to it.

- They define the protection scope; they must be based on the description, i.e., one cannot have protection for a claim that has not been described. This last condition is the judge’s prerogative. A patent can be granted but if there is a lack of description, the patent can be subject to an action for annulment before the judge.

- They can be amended voluntarily, several times, as long as the description remains the basis. These amendments are possible at any time, as long as the prior art search by the INPI has not started (i.e., before 5 or 6 months). If the examination of the patent application by the INPI has started, the amendment request will be refused.

1- The technical field of the invention: for example, a car seat.

2- The state of the art: the objective is to expose the nature of the technical problem addressed by the invention and the previous attempts to solve it, i.e., the closest state of the art. It is therefore necessary to identify the previous documents (a document, a publication, an oral communication, a usage, etc.) that has existed until now and that partially answered the problem addressed by the patent. Their disadvantages must be explained in order to introduce the solution that solves them. This makes it possible to draft strategic patent applications taking into account the current state of the art.

3- The detailed description of the claimed invention. It sets out the nature of the invention, its operation mode and its use. It must allow a full understanding of the technical problem to be solved, the solutions provided and their advantages.

4- A brief presentation of the drawings (top view, bottom view, etc.).

5- A detailed description of the implementation method with examples and references to the drawings.

6- The potential industrial applications of the invention: these possibilities of exploitation can exist in all types of industries including agriculture.

The scope of protection conferred by the patent is determined by the claims (Article L.613-2 of the IP Code). The claims therefore define the scope and limits of the patent owner's exclusive rights. The description and drawings serve to interpret the claims.

Each claim takes the form of a numbered paragraph at the end of the patent description and lists a combination of elements and their relationships.

As defined in Article R.612-7 of the IP Code, every claim consists of two parts:

- The preamble which designates the subject matter of the invention (a method, an apparatus, an article, for example, the seats of a vehicle) and mentions its technical characteristics known to the state of the art, which are necessary for the definition of the claimed subject matter;

- The “characterising” part introduced by the expression “characterised by...” or “characterised in that...”. It sets out the technical characteristics that, in conjunction with those in the preamble, are those for which protection is sought. This “characterising” part is the contribution in relation to what had existed before, i.e., the technical characteristics the applicant considers to be new and inventive on the day of filing. It is in this part that will be checked whether or not the elements mentioned are found in the prior art in order to judge the novelty.

The preamble and the “characterising” part therefore constitute the claim that represents the technical solution to the problem.

Claims are of two kinds: independent claims (or main claims) and dependent claims (or sub-claims). Independent claims are the main claims, i.e., they relate to the essential features of the invention. Dependent claims may supplement the independent claims to which they relate with additional technical features. They will always relate to one or more of the main claims with the established formula: “Device according to claim...”.

A patent always contains at least one independent claim, and optionally one or more dependent claims attached by number to an independent claim.

A patent application may therefore contain several independent claims of different categories, which are of two main types, namely the physical product or a process, with possibilities of combination:

- A product with a process and a use;

- A process with a device for carrying out the process (the machine);

- A product, a process and a device (a machine).

These independent claims must be unitary, i.e., the patent can only relate to one inventive concept.

As an example, the claims could be written as follows. The "Preamble" parts (what is already known) are highlighted in blue; the "characterising" parts (novelty that your invention adds to what is already known) in yellow.

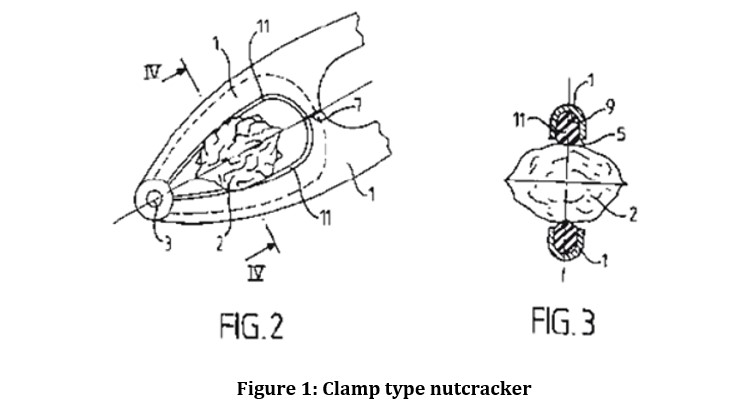

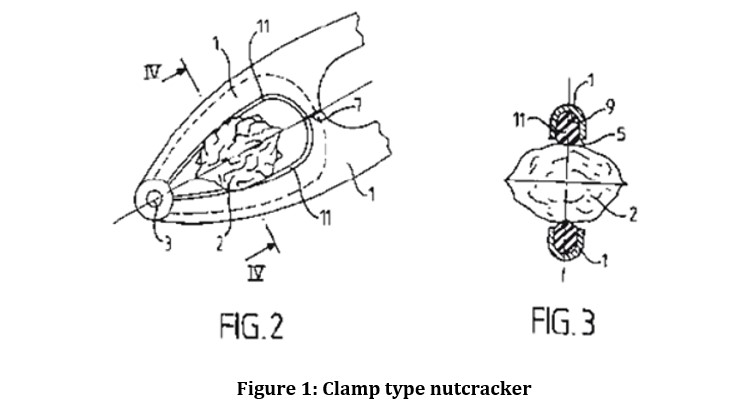

An independent claim does not refer to any other claim. To illustrate this, claim 1, set out below relating to a nutcracker coated with an elastic material, is an independent claim, whereas claim 2 is a dependent claim, because it refers to and clarifies claim 1.

The independent claim:

Claim 1: Device intended to break the shell of fruits such as, in particular, nuts, of the type comprising two elements (1) articulated by one of their respective ends around a transverse axis (3), comprising a zone for gripping the fruit adjacent to the axis of the articulation (3) in which the fruit (2) whose shell it is desired to break is placed, characterised in that at least the internal face (5) of one of these elements is coated, at least in part, with an elastically deformable product (11, 11').

Dependent claims:

Claim 2: A device according to claim (1), characterized in that the inner face (5) of said element is hollowed out with a recess (9) in which is housed, at least in part, said elastically deformable product (11).

Claim 3: A device according to claim (2), characterised in that in the rest position the elastic product (11) projects from the inner face (5) of the element (1) at least over part of the width thereof.

Claim 4: A device according to claim (3), characterized in that the mechanical characteristics of the elastically deformable product (11) and the arrangement thereof within the recess (9) are such that, in the working position, it is retracted into the recess (9) so that the inner face (5) of the element (1) is in contact with the shell of the fruit.

Source

A dependent claim is therefore a claim that refers to a preceding claim and therefore includes all the elements thereof. In the example of the nutcracker, dependent claim 2 does not claim the invention of the head of the nutcracker coated with an elastic material, but claims the head of a nutcracker coated with an elastic material housed in the recess.

Independent claim 1 is therefore broader in scope than dependent claim 2: any nutcracker with a head of elastic material could infringe claim 1, whereas only a nutcracker coated with elastic material housed in the recess could infringe claim 2.

1°) To have a better chance of having a broad patent scope: in order to obtain a patent, the examiner examines the independent claim. If she finds it patentable, then she does not examine the dependent claims. But if the examiner finds a document that claims or discloses a nutcracker with a head of elastic material of claim 1, claim 1 is not patentable. So, she will examine claim 2 and look for documents that might claim or disclose claim 2. Thus, on examination of the file, the dependent claim gives patentable alternatives if claim 1 is not. However, the scope of the patent will be reduced.

2°) To have an alternative in case of a challenge to the validity of the granted patent, called an invalidity action: once the patent is granted, it is presumed to be valid but it can still be attacked by a third party for invalidity, if the latter has found a document that already existed at the time of filing of the patent and that discloses for example claim 1 (the examiner not having found this document during the examination phase). If claim 1 is indeed declared invalid by a judge, then the dependent claim may be used if the document found does not mention the position of the elastic material in the recess. If claim 2 remains valid and it is possible to combine claim 1 and claim 2 to obtain a claim, then this claim, albeit of lesser scope, will be valid. The dependent claim can therefore also be useful in third party invalidity proceedings.

Note: Assume that the prior document disclosing claim 1 is an issued patent. In order to have a valid patent, we combine our 1 and 2 claims. As a result of this combination, it is obvious that if we implement our patent, we also implement the claim of the prior patent which claims the nutcracker coated with an elastic material. So, in order to exploit our patent, we would have to obtain an authorisation to exploit the prior patent. This illustrates the fact that a patent is in no way a legal authorisation for its holder to exploit the invention described and protected in the patent.

A patent is an industrial property title that protects an invention and gives its owner the right to prohibit a third party from exploiting the invention.

A basic rule to remember:

a patent allows its owner to prohibit third parties from exploiting the invention protected by this patent; but a patent is in no case a legal authorisation for its owner to exploit the invention described and protected in the patent! Indeed, this patent may implement another invention protected by another patent. Before any exploitation, it is therefore necessary to study the freedom to exploit the patent.A patent confers its holder an exploitation monopoly for a limited period of time (20 years) in return for the disclosure of the invention 18 months after filing. As a reminder (see P for patent: the basics), a patent describes a new technical solution that makes it possible to solve a technical problem that has not yet been solved or has been partially solved but with disadvantages that are overcome by the new solution.

The patent text:

The text of the patent consists of several essential and complementary parts:- A description of the invention in its entirety, with a brief presentation of the drawings, if any. Drawings are not mandatory. The description sets out what is protected and what is free.

- Claims which define the legal protection scope and delimit the exploitation monopoly held by the patent holder. Not everything described in the patent is in the claims.

The patent also contains a summary of the invention. This summary has no legal value. The claims cannot be based on it. The summary must include the invention title, a concise summary of the essential features (it is practically a copy and paste of the first claim) and possibly indications as to the use of the invention. It may be accompanied by a figure.

The “Description” part:

- It must be clear and complete (Article L.612-5 of the Intellectual Property Code): clear means that one must be able to understand it; complete means that the person skilled in the art must be able to make the invention.- The description may be supplemented by drawings: it must enable the person skilled in the art to make the invention.

- Once the patent is filed, the description is intangible. No technical elements can be added to it.

The “Claims” section:

- The claims must be clear and concise (L612-6 of the IP Code);- They define the protection scope; they must be based on the description, i.e., one cannot have protection for a claim that has not been described. This last condition is the judge’s prerogative. A patent can be granted but if there is a lack of description, the patent can be subject to an action for annulment before the judge.

- They can be amended voluntarily, several times, as long as the description remains the basis. These amendments are possible at any time, as long as the prior art search by the INPI has not started (i.e., before 5 or 6 months). If the examination of the patent application by the INPI has started, the amendment request will be refused.

Preparing the application:

A patent application must be carefully drafted. The description must include several essential elements (article R.612-12 of the Intellectual Property Code) and follow a plan for drafting a patent application:1- The technical field of the invention: for example, a car seat.

2- The state of the art: the objective is to expose the nature of the technical problem addressed by the invention and the previous attempts to solve it, i.e., the closest state of the art. It is therefore necessary to identify the previous documents (a document, a publication, an oral communication, a usage, etc.) that has existed until now and that partially answered the problem addressed by the patent. Their disadvantages must be explained in order to introduce the solution that solves them. This makes it possible to draft strategic patent applications taking into account the current state of the art.

3- The detailed description of the claimed invention. It sets out the nature of the invention, its operation mode and its use. It must allow a full understanding of the technical problem to be solved, the solutions provided and their advantages.

4- A brief presentation of the drawings (top view, bottom view, etc.).

5- A detailed description of the implementation method with examples and references to the drawings.

6- The potential industrial applications of the invention: these possibilities of exploitation can exist in all types of industries including agriculture.

The claims:

The claims define the subject matter of the protection sought (Article L.612-6 of the Intellectual Property Code). As mentioned above, they must be clear and concise and based on the description. They cannot claim what has not been described, nor can they claim what is contained in the summary.The scope of protection conferred by the patent is determined by the claims (Article L.613-2 of the IP Code). The claims therefore define the scope and limits of the patent owner's exclusive rights. The description and drawings serve to interpret the claims.

Each claim takes the form of a numbered paragraph at the end of the patent description and lists a combination of elements and their relationships.

As defined in Article R.612-7 of the IP Code, every claim consists of two parts:

- The preamble which designates the subject matter of the invention (a method, an apparatus, an article, for example, the seats of a vehicle) and mentions its technical characteristics known to the state of the art, which are necessary for the definition of the claimed subject matter;

- The “characterising” part introduced by the expression “characterised by...” or “characterised in that...”. It sets out the technical characteristics that, in conjunction with those in the preamble, are those for which protection is sought. This “characterising” part is the contribution in relation to what had existed before, i.e., the technical characteristics the applicant considers to be new and inventive on the day of filing. It is in this part that will be checked whether or not the elements mentioned are found in the prior art in order to judge the novelty.

The preamble and the “characterising” part therefore constitute the claim that represents the technical solution to the problem.

Claims are of two kinds: independent claims (or main claims) and dependent claims (or sub-claims). Independent claims are the main claims, i.e., they relate to the essential features of the invention. Dependent claims may supplement the independent claims to which they relate with additional technical features. They will always relate to one or more of the main claims with the established formula: “Device according to claim...”.

A patent always contains at least one independent claim, and optionally one or more dependent claims attached by number to an independent claim.

A patent application may therefore contain several independent claims of different categories, which are of two main types, namely the physical product or a process, with possibilities of combination:

- A product with a process and a use;

- A process with a device for carrying out the process (the machine);

- A product, a process and a device (a machine).

These independent claims must be unitary, i.e., the patent can only relate to one inventive concept.

Examples of independent and dependent claims:

As an example, the claims could be written as follows. The "Preamble" parts (what is already known) are highlighted in blue; the "characterising" parts (novelty that your invention adds to what is already known) in yellow.

An independent claim does not refer to any other claim. To illustrate this, claim 1, set out below relating to a nutcracker coated with an elastic material, is an independent claim, whereas claim 2 is a dependent claim, because it refers to and clarifies claim 1.

The independent claim:

Claim 1: Device intended to break the shell of fruits such as, in particular, nuts, of the type comprising two elements (1) articulated by one of their respective ends around a transverse axis (3), comprising a zone for gripping the fruit adjacent to the axis of the articulation (3) in which the fruit (2) whose shell it is desired to break is placed, characterised in that at least the internal face (5) of one of these elements is coated, at least in part, with an elastically deformable product (11, 11').

Dependent claims:

Claim 2: A device according to claim (1), characterized in that the inner face (5) of said element is hollowed out with a recess (9) in which is housed, at least in part, said elastically deformable product (11).

Claim 3: A device according to claim (2), characterised in that in the rest position the elastic product (11) projects from the inner face (5) of the element (1) at least over part of the width thereof.

Claim 4: A device according to claim (3), characterized in that the mechanical characteristics of the elastically deformable product (11) and the arrangement thereof within the recess (9) are such that, in the working position, it is retracted into the recess (9) so that the inner face (5) of the element (1) is in contact with the shell of the fruit.

Source

A dependent claim is therefore a claim that refers to a preceding claim and therefore includes all the elements thereof. In the example of the nutcracker, dependent claim 2 does not claim the invention of the head of the nutcracker coated with an elastic material, but claims the head of a nutcracker coated with an elastic material housed in the recess.

Independent claim 1 is therefore broader in scope than dependent claim 2: any nutcracker with a head of elastic material could infringe claim 1, whereas only a nutcracker coated with elastic material housed in the recess could infringe claim 2.

Drafting tips: why draft an independent claim and a dependent claim? How to structure them?

1°) To have a better chance of having a broad patent scope: in order to obtain a patent, the examiner examines the independent claim. If she finds it patentable, then she does not examine the dependent claims. But if the examiner finds a document that claims or discloses a nutcracker with a head of elastic material of claim 1, claim 1 is not patentable. So, she will examine claim 2 and look for documents that might claim or disclose claim 2. Thus, on examination of the file, the dependent claim gives patentable alternatives if claim 1 is not. However, the scope of the patent will be reduced.2°) To have an alternative in case of a challenge to the validity of the granted patent, called an invalidity action: once the patent is granted, it is presumed to be valid but it can still be attacked by a third party for invalidity, if the latter has found a document that already existed at the time of filing of the patent and that discloses for example claim 1 (the examiner not having found this document during the examination phase). If claim 1 is indeed declared invalid by a judge, then the dependent claim may be used if the document found does not mention the position of the elastic material in the recess. If claim 2 remains valid and it is possible to combine claim 1 and claim 2 to obtain a claim, then this claim, albeit of lesser scope, will be valid. The dependent claim can therefore also be useful in third party invalidity proceedings.

Note: Assume that the prior document disclosing claim 1 is an issued patent. In order to have a valid patent, we combine our 1 and 2 claims. As a result of this combination, it is obvious that if we implement our patent, we also implement the claim of the prior patent which claims the nutcracker coated with an elastic material. So, in order to exploit our patent, we would have to obtain an authorisation to exploit the prior patent. This illustrates the fact that a patent is in no way a legal authorisation for its holder to exploit the invention described and protected in the patent.